Open Expense Policy

I wrote a post the other day about innovating employee benefits practices, and I realized I’d never documented a couple other ways in which we have always tried to innovate People practices. Here’s one of them: the Open Expense Policy, which I wrote about in the second edition of Startup CEO in a new chapter on Authentic Leadership when talking about the problem of the “Say-Do” gap. Here’s what I wrote:

I’ll give you an example that just drove me nuts early in my career here, though there are others in the book. I worked for a company that had an expense policy – one of those old school policies that included things like “you can spend up to $10 on a taxi home if you work past 8 pm unless it’s summer when it’s still light out at 8 pm” (or something like that). Anyway, the policy stipulated a max an employee could spend on a hotel for a business trip, but the CEO (who was an employee) didn’t follow that policy 100% of the time. When called out on it, did the CEO apologize and say they would follow the policy just like everyone else? No, the CEO changed the policy in the employee handbook so that it read “blah blah blah, other than the CEO, President, or CFO, who may spend a higher dollar amount at his discretion.”

When we started Return Path, we had a similar policy. It was standard issue. But then over time as our culture became stronger and our People First philosophy and approach became something we evangelized more, we realized that traditional expense was at odds with our deeply held value of trusting employees to make good decisions and giving them the freedom and flexibility they needed to do their best work.

So we blew up the traditional policy and replaced it with a very simple one — “use your best judgment on expenses and try to spend the company’s money like it’s your own.” That policy is still in place today for our team at Bolster. We do have people sign off on expense requests that come in through the Expensify system, mostly because we have to, but unless there is something extremely profligate, no one really says a word.

Similar to what happened when we switched to an Open Vacation policy, we had some concerns from managers about employees abusing the new un-policy, so we had to assure them we’d have their back. But do you know what happened when we implemented the new policy? We got a bunch of emails from team members thanking us for trusting them with the company’s money. And the average amount of expenses per employees went down. That’s right, down. Trusting people to exercise good judgment and spend the company’s money as if it was their own drove people to think critically about expenses as opposed to “spend to the limit.”

I don’t think in 15+ years of operating with an Open Expense policy that any of us have had to call out an employee’s expenses as being too high more than once or twice. That’s what the essence of employee trust is about. Manage exceptions on the back end, don’t attempt to control or micromanage behavior on the front end.

What a CEO Should Do

Fred Wilson wrote an iconic blog post years ago entitled What a CEO does. In it, he outlined three broad themes:

A CEO does only three things. Sets the overall vision and strategy of the company and communicates it to all stakeholders. Recruits, hires, and retains the very best talent for the company. Makes sure there is always enough cash in the bank.

I wrote a response in a post entitled What Does a CEO Do, Anyway?, in which I added some specificity to those three items and added three key behaviors of successful CEOs. I also added to Fred’s list when I wrote Startup CEO, CEOs have to build and lead a board of directors, CEOs have to manage themselves, and CEOs ultimately have to think about and execute exits.

But recently, as I’ve been coaching a few CEOs, I’ve answered the question differently, because the questions have been a little less about the broad themes and more about how to prioritize — how to know what NOT to do. So in addition to Fred’s wisdom and my other thoughts above, here’s the answer I’m giving CEOs these days:

- First, do what you MUST do. There are some things that are in your job description. Do them first. You have to run your board meeting. You have to pitch investors. You have to write performance reviews for your direct reports.

- Second, do what ONLY YOU can do. There are also some things that, while not in your job description, are things that CEOs and/or founders have special impact when they do. No one can call a team member who just lost a parent or spouse and offer support and sympathy like you can. No one can get on a plane and save a key customer from leaving you like you can. No one can congratulate a sales rep on a key win like you can.

- Third, do what you’re BEST IN CLASS at. Finally, there are things that may be in other people’s job descriptions, but where you’re the stronger executer. I remember reading years ago that Bill Gates, long after he even stopped being CEO of Microsoft and was Chairman, still got involved in some major technical architecture decisions and reviews. Whatever your superpower is, or whatever it was when you were in your pre-CEO jobs, there’s no reason not to jump in and help your team excel at (and ideally train/mentor them) whenever you can.

After that, you can fill in the rest of your time with other tasks. In the world of Covey’s big rocks, this is all the sand. All the other things that come by your desk or inbox that people ask of you. They are the least important. Hopefully this is another helpful lens on how CEOs should spend their time.

Second Lap Around the Track

I wrote a little bit about the experience of being a multi-time founder in this post where I talked about the value of things like a hand-picked team, hand-picked cap table, experience that drives efficient execution, and starting with a clean slate. The second lap around the track (and third, and fourth) is really different from the first lap.

Based on what we do at Bolster, and my role currently, I spend a lot of time meeting with CEOs of all sizes and stages and sectors of company, as they’re all clients or prospects or people I’m coaching. Lately, I’ve noticed a distinct set of work and behaviors and desires among CEOs who are multi-time founders and operators that is different from those same things in first-time founders. Not every single multi-time founder has every single one of these traits, but they all have a majority of them and form a pretty common pattern. I’ve noticed this with non-profit founders as well as for-profit ones.

- They have an Easier Time Recruiting team members and investors. That may sound obvious, but there are significant benefits to it. They also tend to have Much Cleaner Cap Tables, because they lived the horrors of a messy cap table when they exited their last company without thinking about that topic ahead of time!

- They have a Big Vision. Once you’ve had an exit, whether successful or not or somewhere in between, you don’t want to focus on something niche. You want to go all-in on a big problem.

- They are interested in creating Portfolio Effect. A number of repeat founders want to start multiple business at the same time, are actually doing it, or are creating some kind of studio model that creates multiple businesses. Once you have a big team, a track record with investors, and a field of deep expertise, it’s interesting to think about creating multiple related paths (and hedges) to success.

- They are driving to be Efficient in Execution and Find Leverage wherever they can. One multi-time founder I talked to a few weeks ago was bragging to me about how few people he has in his finance team. At Bolster, our objective is to build a big business on a small team, looking for opportunities to use our own network of fractional and project-based team members wherever possible.

- They are Impatient for Progress. While being mindful that good software takes time to build no matter how many engineers you hire, repeat founders tend to have fleshed out their vision a couple layers deep and are always eager to be 6 months ahead of where they are in terms of execution, which leads me to the next point, that…

- They are equally Impatient for Success (or Failure). More than just wanting to be 6 months ahead of where they are in seeing their vision come to life, they want to get to “an answer” as soon as possible. No one likes wasting time, but when you’re on your second or third company, you value your time differently. As a friend of mine says in a sales context, “The best answer you can get from a prospect is ‘yes’ – the second best answer you can get is a fast ‘no’.” The same logic applies to success in your nth startup. Succeed or Fail – you want to find out fast.

- They are Calm and Comfortable in Their Own Skin. At this stage in the game, repeat founders are more relaxed. They know their strengths and weaknesses and have no problem bringing in people to shore those things up. They know that if things don’t work out with this one, there’s more to life.

- They are stronger at Self Management. They are more efficient. They exercise more. They sleep more. They spend more time with family and friends. They work fewer hours.

Anyone else ever notice these traits, or others, in repeat founders?

Inquiry vs. Advocacy

My Grandpa Bill used to not want to talk about himself at dinner parties. When one of us asked him why one day, he said, “I already know what I have to say. What I don’t know, is what the other person has to say.”

There are a few principles I learned years ago in a workshop that my coach Marc led for us called Action/Design. I’m going to try writing a few posts about them, and you can find some articles on them here.

Inquiry vs. Advocacy is simple. Understand the balance of when you ask and listen vs. when you speak in a given conversation. Both are important tools in the CEO tool belt.

My rule of thumb is to ask and listen more than you speak. It’s the only way you will learn, collect data on your organization and on your customers and products. Early in your career, you should primarily be Inquiring. Even mid- and later career people who sometimes must be in a position to speak or advocate their point of view benefit most when they ask and listen and learn.

More important, though, Inquiry vs. Advocacy is the best way to guide your communications in a difficult conversation, complex negotiation, or tricky situation. And it’s in those kinds of situations that you actually need to be cognizant that both approaches are important, and you need to know which one to pull out when and pay attention to how others in the conversation are using the two as well. From an article in the resource center I linked to above:

In conversations on complex and controversial issues, when there is a high degree of advocacy and little inquiry, people are unable to learn about the nature of their differences. People may feel the speaker is imposing a view on them without taking into account their perspective, which can lead to either escalating conflict or withdrawal. When there is a high degree of inquiry, but no one is willing to advocate a position, it is difficult for participants to know where the other stands, and the lack of progress can lead people to feel frustrated and impatient. As a participant in a conversation, being aware of the balance of advocacy and inquiry can help you determine how best to contribute at a given time. If you hear that people are advocating but not asking questions, inquire into their views before adding your own. If you hear people asking questions for information but not stating an opinion, advocating your view may help the group move forward.

Inquiry vs. Advocacy has become a cornerstone of how I think about communicating and learning. I like to think I learned it from Grandpa Bill first, but the Action/Design work with my coach, and then years of practice, drove it home.

Learning Loops

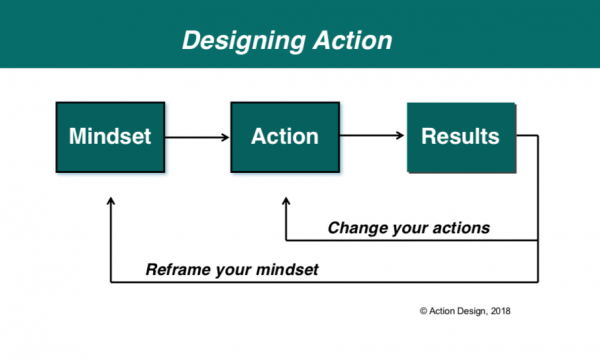

The last couple weeks, I’ve written about tools in the CEO toolbelt that I learned with my coach Marc years ago in a workshop called Action/Design — Inquiry vs. Advocacy, and The Ladder of Inference. The final post in this series is about Learning Loops (or Double Loop Learning if you prefer), popularized by Chris Argyris a couple decades ago.

Here’s the graphic on it:

What’s the tool in the CEO toolbelt here? It’s that every time you’re analyzing a result, you need to analyze it on two levels. Level 1 is the more obvious learning — “What happened…and what do I do next time to produce the same/a different result?” Level 2 is the less obvious learning — “Why did that result happen, and how do I need to think differently about the problem in the future?”

Think about how to apply this to a business result. You put a new pricing plan in place. Clients don’t bite. Loop 1 just gets you something like “ok, let’s try a different pricing plan.” But Loop 2 gets you “how did we come up with the pricing plan that failed in the first place…and how do we generate the next one so we don’t fail?”

Or think of how to apply this to a difficult conversation. You and your VP Eng on why a critical engineer left your organization abruptly. Your VP Eng is blaming Product for poor management of the agile process and product design; you believe it’s an issue of engineering team burnout. You can just go back and forth Advocating your points of view and maybe even Inquiring as to why those points of view exist, and even the powerful Ladder of Inference may not be able to help unless you have a great exit interview. Double Loop Learning is an offramp from that kind of conversation in that you can add that Level 2 questioning to the mix. It’s not about “what do we tweak so another engineer doesn’t leave tomorrow.” It’s “is there a systemic problem here with the way we produce product (or even broader – with our product/market fit) that doesn’t encourage the best team members to stay here?”

The best CEOs are the ones who are constantly listening, learning, adjusting, and executing. Hopefully these three principles — Learning Loops, Inquiry vs. Advocacy, and The Ladder of Inference will all help you on your journey.

Daily Bolster Weeks 1 and 2 recap

We have a little more than two weeks of The Daily Bolster podcast under our belts now, and we’re off to a great start! I announced it here, and I thought I’d post links to the first bunch of episodes…I don’t think I’ll do this regularly, though. You can listen to all episodes here (or on your favorite podcast platform), and never miss an episode when you sign up for daily email notifications.

Episode 1: 3 Tips to Scale Your Culture with Nick Mehta

Our very first guest on The Daily Bolster was Nick Mehta, CEO of Gainsight. As an early-stage startup or a small business, you have significant influence over the culture—but what happens when you’re one of many? Nick and I discussed what happens to company culture when you achieve your scaling and growth goals.

Episode 2: Managing Up with Cristina Miller

Executives are often caught in the middle of the leadership dynamic, managing both up and down the organization. Cristina Miller—a seasoned, results-driven executive and board member (including on Bolster’s board!) with a strong track record—shared what it looks like to set expectations and build a strong relationship with your CEO.

Episode 3: Common Mistakes Founders Make with Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson has been a venture capitalist since 1987 and has worked with me for over 20 years now—so it’s fair to say he’s witnessed a few founders and become familiar with their most common mistakes. Listen to this episode to learn how to recognize and avoid those mistakes for yourself.

Episode 4: Cultivating Talent to Promote Internally with Nick Francis

In this episode, Nick Francis—co-founder and CEO of Help Scout—joins me to discuss what it takes to cultivate in-house talent and embody organizational values. I talk about my playbook for building effective teams and developing leaders with a growth mentality as part of this.

Episode 5: Deep Dive with Jeff Epstein

Career shifts are more common now than ever, even for senior executives. Experienced CFO and operator (and one of my former board members) Jeff Epstein joined me for an extended episode about the ins and outs of career transitions and the surprises that come with them, from role changes to new industries to vastly different organizational structures. Tune in to follow the shifts in Jeff’s career journey, hear about the lessons he learned firsthand, and get his advice for founders looking to scale. “I always wanted to develop a circle of competence and then over time expand the circle,” Jeff says. “You just learn more.”

Episode 6: Hallmarks of Successful Founders with David Cohen

David Cohen, Founder and Chairman at Techstars, shares the top three signs he looks for that differentiate successful founders—things that are nearly impossible to fake. Either you have them, or you don’t. This one is awesome.

Episode 7: Success as a Fractional Exec with Courtney Graeber

If you know anything about Bolster, you know we’re a champion for fractional executives. As an Interim Chief People Officer, HR Executive Consultant, and trusted mentor to executive teams, Courtney Graeber provides feedback and recommendations that enhance organizational culture and attract, develop, and retain top talent. Many of her clients are navigating transitional periods—and that’s where Courtney’s expertise comes in. Listen in to learn what it’s like to be (or work with) a fractional head of people.

Episode 8: 3 Ways VCs Say “No” Without Saying “No” with Jenny Fielding

It’s important for founders to be able to hear what’s left unsaid in conversations with VCs. Sometimes, says one of NYC’s top pre-seed investors Jenny Fielding, VCs aren’t ready to invest in a startup, but they’re not ready to say no, either. Here, Jenny shares three signs a VC may be saying “no” without saying the words—and what founders should do next.

Episode 9: Building a Strong Culture with Jailany Thiaw

Jailany Thiaw, founder and CEO of UPskill, a future-of-work startup automating feedback in entry-level hiring pipelines, joins me to discuss the best ways to get company buy-in as you build and maintain a strong and welcoming culture—especially in an early stage or remote environment.

Episode 10: Deep Dive with Brad Feld

Brad Feld is partner and co-founder of Foundry, and a long time early stage investor and entrepreneur who I’ve also worked with for more than two decades. In this episode, he and I take a deep dive into how startups and venture capital have changed over the past 25 years—and what has stayed the same. They also discuss the dynamics of startup boards, along with common characteristics that make founders or companies successful at scale.

Episode 11: The Value of Podcasting with Lindsay Tjepkema

This episode is all about podcasting. Meta, right? Lindsay Tjepkema is the CEO and co-founder of Casted, the podcasting solution for B2B marketers. She and I dive into the reasons why podcasts are such a great way to get your voice—literally—out into the world. Tune in to hear Lindsay’s tips for starting a podcast as a CEO, setting expectations, asking meaningful questions, and creating human connection. We’ve loved partnering with Lindsay and her team so far on The Daily Bolster!

Episode 12: Interviewing for “Culture Fit” with Rory Verrett

What does it mean to interview for culture fit? How should CEOs and leaders go about doing it—and is there a better way? Rory Verrett is the founder and managing partner of Protégé Search, the leading retained search and leadership advisory firm focused on diverse talent, and is also on Bolster’s Board of Directors. He and I discuss why CEOs are not always the best arbiters of company culture, then we dive into what it means to look for specific values throughout the interview process, rather than the vague concept of a culture fit.

The Daily Bolster is for people in the startup world want to hear from industry experts of all backgrounds, but don’t always have the time to listen to full length interviews, even at 2x speed. Instead, we’re getting straight to the point with mostly 5-minute episodes. Any and all feedback welcome!

The Dowry

Here’s one to keep in mind – we did this a few times at Return Path, and I was just reminded of it when I was coaching another founder who is doing the same thing right now.

Sometimes when you’re doing a strategic acquisition and it’s an all-stock deal, you can insist as a term of the acquisition that the target company’s investors invest more capital into your company.

That’s right, not only do you not have to put cash OUT for the deal, you’re getting additional cash IN. Think of it as a contemporary corporate version of the dowry.

Why would the cap table of the target company agree to this? Here are a few reasons:

- you’re in a strong enough negotiating position – best home for the business, best chance of the target company investors getting a return

- the target company investors have more dry powder and want to double down – they love your vision for the combined company

- you’re only offering the target company investors common stock in the deal, and they are pushing hard to get preferred

The Dowry is not something you can get to with every deal, and you might not need it. But think of it as a tool in the M&A/financing tool belt.

The Art of the Post-Mortem

The Art of the Post-Mortem

It has a bunch of names — the After-Action Review, the Critical Incident Review, the plain old Post-Mortem — but whatever you call it, it’s an absolute management best practice to follow when something has gone wrong. We just came out of one relating to last fall’s well document phishing attack, and boy was it productive and cathartic.

In this case, our general takeaway was that our response went reasonably well, but we could have been more prepared or done more up front to prevent it from happening in the first place. We derived some fantastic learnings from the Post-Mortem, and true to our culture, it was full of finger-pointing at oneself, not at others, so it was not a contentious meeting. Here are my best practices for Post-Mortems, for what it’s worth:

- Timing: the Post-Mortem should be held after the fire has stopped burning, by several weeks, so that members of the group have time to gather perspective on what happened…but not so far out that they forget what happened and why. Set the stage for a Post-Mortem while in crisis (note publicly that you’ll do one) and encourage team members to record thoughts along the way for maximum impact

- Length: the Post-Mortem session has to be at least 90 minutes, maybe as much as 3 hours, to get everything out on the table

- Agenda format: ours includes the following sections…Common understanding of what happened and why…My role…What worked well…What could have been done better…What are my most important learnings

- Participants: err on the wide of including too many people. Invite people who would learn from observing, even if they weren’t on the crisis response team

- Use an outside facilitator: a MUST. Thanks to Marc Maltz from Triad Consulting, as always, for helping us facilitate this one and drive the agenda

- Your role as leader: set the tone by opening and closing the meeting and thanking the leaders of the response team. Ask questions as needed, but be careful not to dominate the conversation

- Publish notes: we will publish our notes from this Post-Mortem not just to the team, but to the entire organization, with some kind of digestible executive summary and next actions

When done well, these kinds of meetings not only surface good learnings, they also help an organization maintain momentum on a project that is no longer in crisis mode, and therefore at risk of fading into the twilight before all its work is done. Hopefully that happened for us today.

The origins of the Post-Mortem are with the military, who routinely use this kind of process to debrief people on the front lines. But its management application is essential to any high performing, learning organization.

The Difference Between Culture and Values

The Difference Between Culture and Values

This topic has been bugging me for a while, so I am going to use the writing of this post as a means of working through it. We have a great set of core values here at Return Path. And we also have a great corporate culture, as evidenced by our winning multiple employer of choice awards, including being Fortune Magazine’s #2 best medium-sized workplace in America.

But the two things are different, and they’re often confused. I hear statements all the time, both here and at other companies, like “you can’t do that — it’s not part of our culture,” “I like working there, because the culture is so great,” and “I hope our culture never changes.” And those statements reveal the disconnect.

Here’s my stab at a definition. Values guide decision-making and a sense of what’s important and what’s right. Culture is the collection of business practices, processes, and interactions that make up the work environment.

A company’s values should never really change. They are the bedrock underneath the surface that will be there 10 or 100 years from now. They are the uncompromising core principles that the company is willing to live and die by, the rules of the game. To pick one value, if you believe in Transparency one day, there’s no way the next day you decide that being Transparent is unimportant. Can a value be changed? I guess, either a very little bit at a time, slowly like tectonic plates move, or in a sharp blow as if you deliberately took a jackhammer to stone and destroyed something permanently. One example that comes to mind is that we added a value a couple years back called Think Global, Act Local, when we opened our first couple of international offices. Or a startup that quickly becomes a huge company might need to modify a value around Scrappiness to make it about Efficiency. Value changes are few and far between.

If a company’s values are its bedrock, then a company’s culture is the shifting landscape on top of it. Culture is the current embodiment of the values as the needs of the business dictate. Landscapes change over time — sometimes temporarily due to a change in seasons, sometimes permanently due to a storm or a landslide, sometimes even due to human events like commercial development or at the hand of a good gardener.

So what does it mean that culture is the current embodiment of the values as the needs of the business dictate? Let’s go back to the value of Transparency. When you are 10 people in a room, Transparency means you as CEO may feel compelled to share that you’re thinking about pivoting the product, collect everyone’s point of view on the subject, and make a decision together. When you are 100 people, you probably wouldn’t want to share that thinking with ALL until it’s more baked, you have more of a concrete direction in mind, and you’ve stress tested it with a smaller group, or you risk sending people off in a bunch of different directions without intending to do so. When you are 1,000 employees and public, you might not make that announcement to ALL until it’s orchestrated with your earnings call, but there may be hundreds of employees who know by then. A commitment to Transparency doesn’t mean always sharing everything in your head with everyone the minute it appears as a protean thought. At 10 people, you can tell everyone why you had to fire Pat – they probably all know, anyway. At 100 people, that’s unkind to Pat. At 1,000, it invites a lawsuit.

Or here’s another example. Take Collaboration as a value. I think most people would agree that collaboration managed well means that the right people in the organization are involved in producing a piece of work or making a decision, but that collaboration managed poorly means you’re constantly trying to seek consensus. The culture needs to shift over time in order to make sure the proper safeguards are in place to prevent collaboration from turning into a big pot of consensus goo – and the safeguards required change as organizations scale. In a small, founder-driven company, it often doesn’t matter as much if the boss makes the decisions. The value of collaboration can feel like consensus, as they get to air their views and feel like they’re shaping a decision, even though in reality they might not be. In a larger organization with a wider range of functional specialists managing their own pieces of the organization, the boss doesn’t usually make every major decision, though guys like Ellison, Benioff, Jobs, etc. would disagree with that. But in order for collaboration to be effective, decisions need to be delegated and appropriate working groups need to be established to be clear on WHO is best equipped to collaborate, and to what extent. Making these pronouncements could come as feeling very counter-cultural to someone used to having input, when in fact they’re just a new expression of the same value.

I believe that a business whose culture never evolves slowly dies. Many companies are very dynamic by virtue of growth or scaling, or by being in very dynamic markets even if the company itself is stable in people or product. Even a stable company — think the local hardware store or barber shop — will die if it doesn’t adapt its way of doing business to match the changing norms and consumption patterns in society.

This doesn’t mean that a company’s culture can’t evolve to a point where some employees won’t feel comfortable there any longer. We lost our first employee on the grounds that we had “become too corporate” when we reached the robust size of 25 employees. I think we were the same company in principles that day as we had been when we were 10 people (and today when we are approaching 500), but I understood what that person meant.

My advice to leaders: Don’t cling to every aspect of the way your business works as you scale up. Stick to your core values, but recognize that you need to lead (or at least be ok with) the evolution of your culture, just as you would lead (or be ok with) the evolution of your product. But be sure you’re sticking to your values, and not compromising them just because the organization scales and work patterns need to change. A leader’s job is to embody the values. That impacts/produces/guides culture. But only the foolhardy leaders think they can control culture.

My advice to employees: Distinguish between values and culture if you don’t like something you see going on at work. If it’s a breach of values, you should feel very free to wave your arms and cry foul. But if it’s a shifting of the way work gets done within the company’s values system, give a second thought to how you complain about it before you do so, though note that people can always interpret the same value in different ways. If you believe in your company’s values, that may be a harder fit to find and therefore more important than getting comfortable with the way those values show up.

Note: I started writing this by talking about the foundation of a house vs. the house itself, or the house itself vs. the furniture inside it. That may be a more useful analogy for you. But hopefully you get the idea.

Turning Lemons into Lemonade

I’ve always thought that the ability to stare down adversity in business — or turning lemons into lemonade, as a former boss of mine used to say — is a critical part of being a mature professional. We had a prime example of this a couple weeks ago at Return Path.

We had scheduled a webinar on email deliverability, a critical topic for our market, and the moment of the webinar had come, with over 100 clients and prospects on the line for the audio and web conference. There was a major technical glitch with our provider, Webex (no link for you, Webex), and after 5 or 10 minutes, we had to cancel the webinar — telling all 100 members of our target audience that we were sorry, we’d have to reschedule. What a nightmare! Even worse, Webex displayed atrocious customer service to us, not apologizing for the problem, blaming it on us (as if somehow it was our fault that half the people on the line couldn’t hear anything), and not offering us any compensation for the situation.

As you can imagine, our marketing guru Jennifer Wilson was devastated. But instead of sulking, she turned the situation on its head. She rescheduled the event for three weeks out with a different provider who was technically competent and a pleasure to work with, Raindance, and sent every person who’d been on our aborted webinar a gift certificate to Starbucks so they could enjoy a snack on our dime during the rescheduled event. Not only did we have full attendance at the rescheduled event, but Jennifer received dozens of emails from clients sympathizing with her, commending her on her attitude, and of course thanking her for the free latte.

It’s hard to do, and you hate to have to do it, but successfully turning lemons into lemonade is one of the most satisfying feelings in business!

People rarely comment on this blog (or most non-political blogs, I’ve noticed), so feel free to share your best lemons-to-lemonade story with me in a comment, and I promise I’ll post the best couple of them pronto!

Books

I’ve published two editions of Startup CEO, a sequel called Startup CXO, and am a co-author on the second edition of Startup Boards. We also just (2025) published mini-book versions of Startup CXO specifically for five individual functions, Startup CFO, Startup CRO, Startup CMO, Startup CPO, and Startup CTO.

You’re only a startup CEO once. Do it well with Startup CEO, a “master class in building a business.”

—Dick Costolo, Partner at 01A (Former CEO, Twitter)

Being a startup CEO is a job like no other: it’s difficult, risky, stressful, lonely, and often learned through trial and error. As a startup CEO seeing things for the first time, you’re likely to make mistakes, fail, get things wrong, and feel like you don’t have any control over outcomes.

As a Startup CEO myself, I share my experience, mistakes, and lessons learned as I guided Return Path from a handful of employees and no revenues to over $100 million in revenues and 500 employees.

Startup CEO is not a memoir of Return Path’s 20-year journey but a CEO-focused book that provides first-time CEOs with advice, tools, and approaches for the situations that startup CEOs will face.

You’ll learn:

How to tell your story to new hires, investors, and customers for greater alignment How to create a values-based culture for speed and engagement How to create business and personal operating systems so that you can balance your life and grow your company at the same time How to develop, lead, and leverage your board of directors for greater impact How to ensure that your company is bought, not sold, when you exit

Startup CEO is the field guide every CEO needs throughout the growth of their company and the one I wish I had.

“Startup CXO is an amazing resource for CEOs but also for functional leaders and professionals at any stage of their career.”

– Scott Dorsey, Managing Partner, High Alpha (Former CEO, ExactTarget)

One of the greatest challenges for startup teams is scaling because usually there’s not a blueprint to follow, people are learning their function as they go, and everyone is wearing multiple hats. There can be lots of trial and error, lots of missteps, and lots of valuable time and money squandered as companies scale. My team and I understand the scaling challenges—we’ve been there, and it took us nearly 20 years to scale and achieve a successful exit. Along the way we learned what worked and what didn’t work, and we share these lessons learned in Startup CXO.

Unlike other business books, Startup CXO is designed to help each functional leader understand how their function scales, what to anticipate as they scale, and what things to avoid. Beyond providing function-specific advice, tools, and tactics, Startup CXO is a resource for each team member to learn about the other functions, understand other functional challenges, and get greater clarity on how to collaborate effectively with the other functional leads.

CEOs, Board members, and investors have a book they can consult to pinpoint areas of weakness and learn how to turn those into strengths. Startup CXO has in-depth chapters covering the nine most common functions in startups: finance, people, marketing, sales, customers, business development, product, operations, and privacy. Each functional section has a “CEO to CEO Advice” summary from me on what great looks like for that CXO, signs your CXO isn’t scaling, and how to engage with your CXO.

Startup CXO also has a section on the future of executive work, fractional and interim roles. Written by leading practitioners in the newly emergent fractional executive world, each function is covered with useful tips on how to be a successful fractional executive as well as what to look for and how to manage fractional executives.

A comprehensive guide on creating, growing, and leveraging a board of directors written for CEOs, board members, and people seeking board roles.

The first time many founders see the inside of a board room is when they step in to lead their board. But how do boards work? How should they be structured, managed, and leveraged so that startups can grow, avoid pitfalls, and get the best out of their boards? Authors Brad Feld, Mahendra Ramsinghani, and Matt Blumberg have collectively served on hundreds of startup and scaleup boards over the past 30 years, attended thousands of board meetings, encountered multiple personalities and situations, and seen the good, bad, and ugly of boards.

In Startup Boards: A Field Guide to Building and Leading an Effective Board of Directors, the authors provide seasoned advice and guidance to CEOs, board members, investors, and anyone aspiring to serve on a board. This comprehensive book covers a wide range of topics with relevant tips, tactics, and best practices, including:

- Board fundamentals such as the board’s purpose, legal characteristics, and roles and functions of board members;

- Creating a board including size, composition, roles of VCs and independent directors, what to look for in a director, and how to recruit directors;

- Compensating, onboarding, removing directors, and suggestions on building a diverse board;

- Preparing for and running board meetings;

- The board’s role in transactions including selling a company, buying a company, going public, and going out of business;

- Advice for independent and aspiring directors.

Startup Boards draws on the authors’ experience and includes stories from board members, startup founders, executives, and investors. Any CEO, board member, investor, or executive interested in creating an active, involved, and engaged board should read this book—and keep it handy for reference.

Five new mini-books from Startup CXO, but with new bonus material and an obvious focus on each specific functional area.

Each book has several topics in common – chapters on the nature of an executive’s role, how a fractional person works in that role, how the role works with the leadership team, how to hire that role, how the role works in the beginning of a startup’s life, how the role scales over time, and CEO:CEO advice about managing the role.

In Startup CTO (Technology and Product), the role-specific topics Shawn Nussbaum talks about are The Product Development Leaders, Product Development Culture, Technical Strategy, Proportional Engineering Investment and Managing Technical Debt, Shifting to a New Development Culture, Starting Things, Hiring Product Development Team Members, Increasing the Funnel and Building Diverse Teams, Retaining and Career Pathing People, Hiring and Growing Leaders, Organizing Collaborating with and Motivating Effective Teams, Due Diligence and Lessons Learned from a Sale Process, Selling Your Company, Preparation, and Selling Your Company/Telling the Story.

In Startup CMO, the role-specific topics Nick Badgett and Holly Enneking talk about are Generating Demand for Sales, Supporting the Company’s Culture, Breaking Down Marketing’s Functions, Events, Content & Communication, Product Marketing, Marketing Operations, Sales Development, and Building a Marketing Machine.

In Startup CFO, the role-specific topics Jack Sinclair talks about are Laying the CFO Foundation, Fundraising, Size of Opportunity, Financial Plan, Unit Economics and KPIs, Investor Ecosystem Research, Pricing and Valuation, Due Diligence and Corporate Documentation, Using External Counsel, Operational Accounting, Treasury and Cash Management, Building an In-House Accounting Team, International Operations, Strategic Finance, High Impact Areas for the Startup CFO as Partner, Board and Shareholder Management, Equity, and M&A.

In Startup CRO, the role-specific topics Anita Absey talks about are Hiring the Right People, Profile of Successful Sales People, Compensation, Pipeline, Scaling the Sales Organization, Sales Culture, Sales Process and Methodology, Sales Operating System, Marketing Alignment, Market Assessment & Alignment, Channels, Geographic Expansion, and Packaging & Pricing.

In Startup CPO (HR/People), the role-specific topics Cathy Hawley talks about are Values and Culture, Diversity Equity and Inclusion, Building Your Team, Organizational Design and Operating Systems, Team Development, Leadership Development, Talent and Performance Management, Career Pathing, Role Specific Learning and Development, Employee Engagement, Rewards and Recognition, Reductions in Force, Recruiting, Onboarding, Compensation, People Operations, and Systems.